With school admissions in Mumbai for the new academic year in full swing, parents from different socio-economic backgrounds are scrambling to secure seats for their children in the best schools. The opportunities for those from financially and socially disadvantaged backgrounds, however, are not equal. This is where the Right to Education (RTE) Act was supposed to come in – allowing more children a chance at equal education.

Introduced in 2009, Section 12 (1)(C) of the Act mandates 25% reservations in private, unaided, non-minority schools for those from disadvantaged backgrounds and economically weaker sections. This includes students with disabilities, those from scheduled castes (SC), scheduled tribes (ST) and religious minorities and those from families with an annual income under Rs 1 lakh (in Maharashtra).

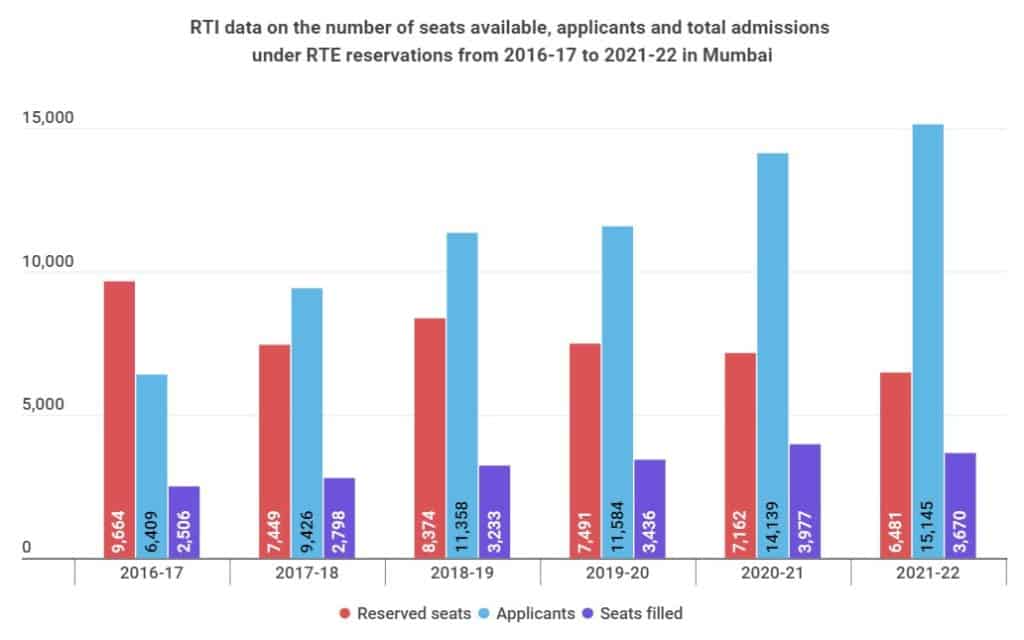

But despite the fact that applicants outnumber reservations, in the end, only about half the seats are filled.

According to an RTI response, 15,143 parents sent in applications for the 6,481 seats available under reservation in Mumbai in 2021-22. But, only 3,670 were admitted. As a result, the admission rate was a measly 25%, while nearly half of the reserved seats remained vacant.

The pattern is no different for the years before. In 2020-21, there were 7,162 admission spots available. 14,139 students applied, but only 3,977 got in.

Pre-pandemic, in the years 2019-20, awareness about the reservations in schools under RTE was lower, hence fewer parents, exactly 11,584, applied. Despite over 7,000 seats under the quota, only 3,436 were successful in enrolling in the schools.

“The 25% RTE reservations haven’t worked out well. There are a lot of issues with access,” says Farida Lambey, co-founder of Pratham, an NGO working in the field of education. Behind these discrepancies is a mix of institutional, fiscal and social reasons that restricts those trying to get admitted under RTE because of their socio-economic positions. For the 23,978 students that applied for the seats this year, the story is likely to be the same.

Applying for seats under 25% RTE reservations

The process for admissions in the schools under RTE is long. Student applications are invited in February, and admissions continue till December-January. The school year, on the other hand, starts latest in June, with several international, CBSE and ICSE schools starting early in March. To cut this delay short, the Maharashtra education department has fixed a deadline of September 30th for this year.

The application and subsequent selection process is also entirely online in an attempt to ensure transparency, posing accessibility issues for those poorly educated or without internet devices. “99.9% of the time the website doesn’t work or is glitchy,” says Aftab Qureshi, who has applied for the reservation a second time for his 7-year-old son Mohammed Ashar.

Because of his experience and information obtained through YouTube, Aftab also lent a helping hand to his friends applying for their children.

“How well you fill the government form is very important,” says Sufiyan Vanu, a former corporator in the Vadala area who has been helping parents with RTE admissions through his NGO Vanu Foundation since 2016. “The first year I started, I employed a retired government officer for help. Now my 3-person team has the experience, but there are always new things added to the form. For instance, you have to fill in your address and pin it on the map in the exact location.”

Perceiving the need and demand, NGOs and political parties like his organise camps in informal settlements around admission dates to facilitate admissions. Still, only 15,659 of the 23,978 applicants were cleared to move on to the next step, struggling for a seat in the 6,481 available.

Absentees

After the application round, the department of education begins selecting the students for the reserved seats. Schools with applicants fewer or equal to the number of seats available have all applicants pass through. For the rest, students are chosen randomly through a lottery. In the first round, a total of 5,342 students in Mumbai were selected on April 27th.

After the parent receives the SMS confirming their seat, they have to confirm their admissions by visiting the assigned verification centre with their documents. But till the May 10th deadline, after which they would lose their seat, 2,090 of the parents had yet to do so.

Many parents fail to show up, suggests an official from the BMC’s education department who did not want to be named. Many are away in their villages for the summer vacations, or have already secured admissions in a different school. Parents also choose not to show up if they are selected for a school not to their liking, as reputed schools typically are more readily filled. Some do not respond to being contacted due to errors in mobile numbers, and miss the window they have for confirmations.

This is corroborated by Sufiyan. Earlier in the day, an upset mother had approached him due to failing to confirm admission, as she was away due to her mother-in-law’s demise. COVID-19 has also forced families to leave Mumbai, leaving behind a trail of filled forms without their applicants.

“Many that apply live in slums and aren’t very educated, so they aren’t properly aware of the entire process and don’t take the SMS seriously. And when they come, it’s too late,” says Sufiyan. Even though Sufiyan has a dedicated three person team working on RTE admissions and follow ups strictly, ten-fifteen of the selected applications his team facilitated have already dropped out because of these reasons.

Read more: COVID has led to academic learning gaps among kids, but there’s something more worrisome

Documentation

The students that do not get selected in the first round are put on the waiting list. While in the previous years subsquent lottery rounds were held, this time students will be chosen according to their priority number on the waiting list.

This round began in Mumbai on May 20th, and continues till the 27th.

Heena Shaikh is a domestic worker in Govandi, and single mother to 6-year-old Kulsum. Because she wasn’t very educated, she had help throughout the process of applying for RTE. First, her neighbour informed her about the possibility of admissions, and an acquaintance took her along to a camp of registration.

But even as she waits for the SMS confirming the admission, her daughter’s chance depends on her documents.

The documents include: address proof; the student’s birth certificate; proof of disability or income certificate or caste certificate (of the father or student). Single mothers have to furnish divorce court documents or, in the case of a widow, their husband’s death certificate.

But, because Heena’s husband left her when her daughter was just two years old and is estranged from them, she does not have any of his documents. “I had to make my own income certificate and there were some problems, because it isn’t easy to get one if you’re a woman, but someone helped me get it,” she says.

Strict rules governing documentation mean students can lose their seat based on minor technicalities. To illustrate, a student was rejected by a school in 2020, because of an address discrepancy on the Aadhaar card and application form, which the mother alleged was a temporary address due to SRA redevelopment.

The Maharashtra government rules also stipulate that the documents must be issued in Maharashtra, making it harder for migrants.

But these rules also end up being a mechanism for schools to turn the students from low income backgrounds away. “Lately the admissions we manage to get have dropped from 400 to 300, out of the 1,000 applications we help fill, because schools are rejecting a lot of kids indirectly,” says Sufiyan. “They bring up excuses, ask the parents to change or bring more documents and delay the admission till it’s too late.”

How do the schools reject RTE admissions?

Technically, the schools cannot reject applications under RTE. But in practice, they can influence the result in many ways that end in detracting admissions.

Sufiyan recounts an instance where a school’s principal turned up at an applicant’s house in a slum, accusing them of being ineligible for RTE because they had a TV and smartphone. “Why does she think they live in a 10×10 house in a slum if they have so much money? And that’s the job of the verification committee, not the principal,” he says.

Parents are also asked to pay for things other than the admission. “They harass students, asking them to pay for books, bags, uniforms, picnics,” says Sufiyan.

This can take more insidious forms, says Farida, when the schools overtly discourage the students from joining in the interview. “They counsel the children, telling them the school won’t be good for them. Sometimes it’s the message that principals and schools give subtly,” she says.

Farida gives the example of Dhirubai Ambani school, which is located next to a slum. “It can be traumatic for a child from a slum to go to Dhirubai Ambani school, and sit with Shahrukh Khan’s son,” she says. The influences the parents too, preferring not to send their children where there is a big socioeconomic gap, or taking them out. This aversion is higher in older students.

But while the expensive schools are more prone to reject students for these reasons, Sufiyan says that is not an issue in Vadala. “There are 33-34 schools here, and they don’t have a problem teaching poor and well off kids together,” he says. On asking the schools the reason for the rejections, they pointed to the primordial reason: money.

The central and state governments have been sluggish in releasing the money for RTE reimbursement to schools, leaving the schools dry. So, the schools try to minimise their admissions to the extent possible.

Aftaab’s son is 12th on the waiting list. When asked about his backup plan in case his son isn’t selected, he says, “I have an orange ration card, so I will try to avail the Economically Backward Class (EBC) scheme. For that, I will have to pay for admission myself and then submit my application for reimbursement, which takes a long time and doesn’t always go smoothly.”

But with the school reopening date of June 15th fast approaching, he wonders how long he will have to wait.